Summary

In this study, we shed light on the reality of the gas market in the European Union (EU) countries, explaining their degree of dependence on Russian gas in the period before the Russian war on Ukraine, when Moscow monopolized the European gas market. The study also outlined the policies adopted by European countries, which relied on diversifying imports and developing their gas import infrastructure, which contributed to reducing their dependence on Russian gas after 2022. The study concluded that EU countries had not been able to completely end their dependence on Russian gas by the time of writing, but rather had been able to reduce their dependence by more than half compared to what it was before the Ukrainian war. According to the data monitored by the study, Europe’s dependence on Russian gas is expected to significantly decrease in the medium and long term after implementing a set of strategies. The study concluded that Russia is poised to lose its market share in the EU, thereby losing the exports of its most important suppliers. This will have repercussions for the economy and the effectiveness of Russian foreign policy. Russian production will decline in the medium term until the markets in China and Asia are ready to receive Russian gas.

Introduction

For more than two decades, European Union countries have sought to eliminate Russia’s monopoly on the European gas market. However, they have failed to implement numerous international gas pipeline projects, forcing them to rely primarily on natural gas from Russia’s Western Siberian fields. Russia has thus been able to maintain its monopoly on the European gas market by implementing several strategies, the most important of which has been linking the European continent with projects that are highly efficient, technically feasible, and economically viable.

Russia’s monopoly on the European gas market has given it a strategic and sensitive leverage that targets the national security of the European continent. Moscow has repeatedly used gas as a means of pressure on EU countries in the event of any conflict between the two parties, the most recent of which was the Russian war on Ukraine in 2022. Moscow threatened to cut off gas supplies to Europe several times by disrupting the flow of gas through pipelines, citing technical malfunctions. This prompted European countries to insist on finding alternatives to Russian gas, fearing a shortage of their supplies and the emptying of strategic reserves, which could threaten European national, economic, and societal security.

This study attempts to shed light on the reality of energy security for European Union countries from the perspective of the gas market alone, without addressing the oil market. This is based on the importance of gas to the European market and the difficulty of importing it compared to oil for technical reasons, in addition to the European gas market’s historical connection to Russia. The study focuses in detail on the reality of the European gas market and the recent developments in its infrastructure for consuming and importing liquefied natural gas (LNG). This understanding demonstrates their ability to diversify their imports and reduce their dependence on Russian gas in the medium and long term. The study highlights the most prominent alternatives that EU countries see as feasible, both currently and in the future, as an alternative to Russian gas. The final section of the study addresses the potential repercussions for Russia’s energy security in the future, which is expected to lose the largest portion of its market share in EU countries.

First: The reality of the gas market for European Union countries

In this section of the report, we attempt to shed light on the reality of the gas market in the European Union countries, monitoring their degree of dependence on Russian gas compared to total imports and market consumption requirements. This monitoring contributes to identifying and measuring the degree of Russian monopoly over the European market between two periods: the first, specifically before the Russian war on Ukraine in 2021, and the second, after the war in 2023. The comparison process is based on the annual divisions adopted by the European Union, which is “quarterly.” This means we measure gas imports between the second quarter of 2021 and the second quarter of 2023, a measure that provides accurate results regarding the total annual imports.

The European Union consumes 412 billion cubic meters of gas annually[1], which is mainly used for electricity generation, domestic heating, and industrial processes[2]. Half of this amount is imported via pipelines[3], and the highest form of natural gas is ready for consumption. Here, it is necessary to differentiate between natural gas and liquefied gas: Natural gas is imported exclusively via pipelines from production areas to consumption areas, to be distributed directly to internal distribution networks. Importing via pipelines has strategic advantages for both producers and consumers, as it allows for the continuous pumping of large quantities of gas at a low cost. Liquefied gas, on the other hand, requires the construction of liquefaction plants on the coasts of both consuming and producing countries. After being compressed (liquefied), it is exported and shipped via dedicated ships. It is then re-liquefied at liquefaction plants in consumption areas, which are located on the coast or on floating vessels. Importing liquefied natural gas requires significant funding and a longer delivery time, and the amount of gas exported is lower compared to pipeline transportation. In this section of the study, we outline the quantities of gas European countries import via pipelines and liquefaction plants, as each method has implications for European energy security and the extent of European success in reducing dependence on Russian gas.

Pipeline imports

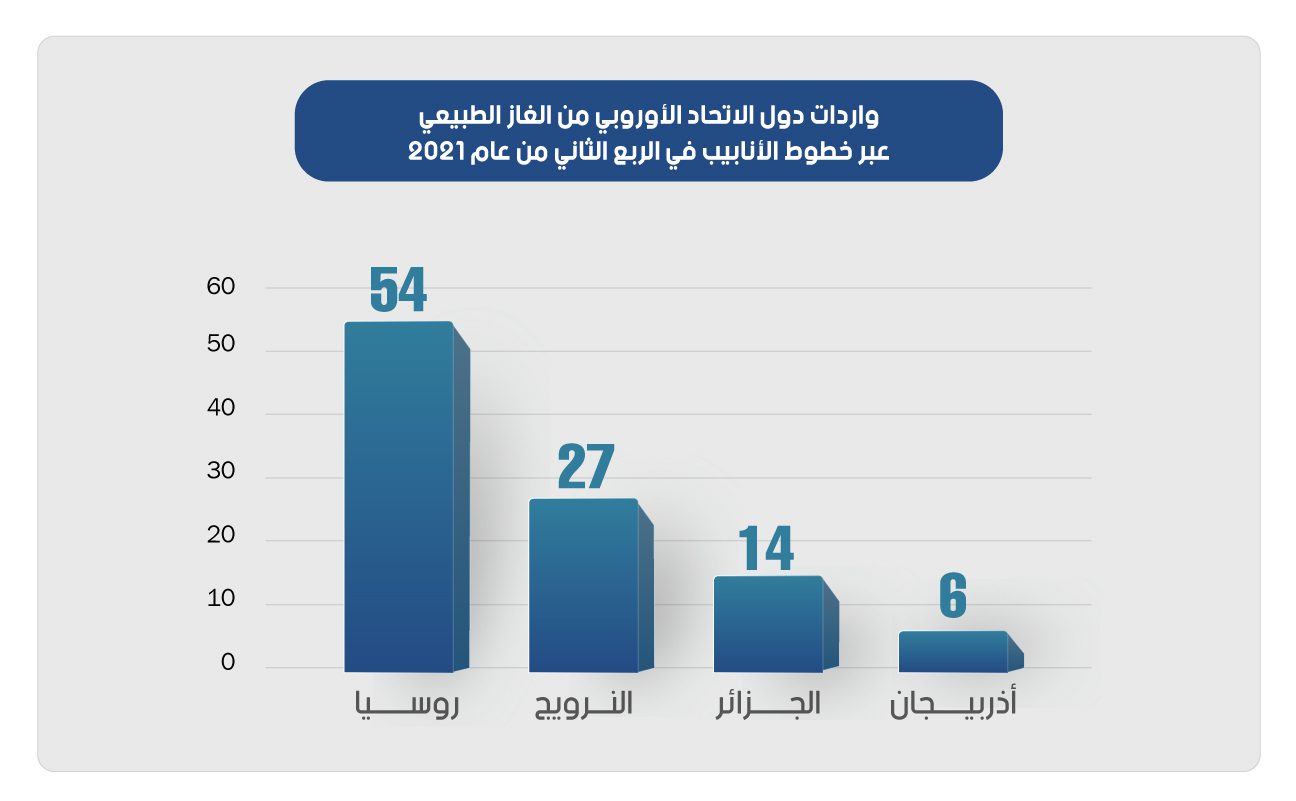

Historically, European Union countries have relied heavily on importing natural gas via a series of pipelines from Russia, which we illustrate at the end of the study in Map No. (1), the map of gas pipelines between Russia and European Union countries. The proportion of European imports via Russian pipelines of total annual needs in 2021 reached approximately 56%, and Figure No. (1) shows the sources of natural gas imports via pipelines for European Union countries in the second quarter of 2021[4].

Figure No. (1) Sources of natural gas imports via pipelines to European Union countries in the second quarter of 2021

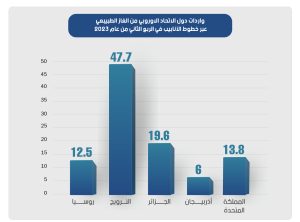

Figure (1) shows us the increase in Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, which amounted to 54% of total imports in the second quarter of 2021. However, this percentage did not continue after the Russian war on Ukraine, as it decreased significantly, as shown in Figure (2), which shows the natural gas imports of the European Union countries in the second quarter of 2023, as the import percentage increased via pipelines coming from Norway, which became the largest exporter of gas via pipelines in the European Union with a share of 47.7% (20.6 billion cubic meters), and Algeria became the second largest exporter with an export share of 19.6% (8.5 billion cubic meters), followed by the United Kingdom (13.8%, 6 billion cubic meters), Russia (12.4%, 5 billion cubic meters), and Azerbaijan (6.5%, 2.8 billion cubic meters[5].

Figure No. (2) Natural gas imports to European Union countries in the second quarter of 2023

The decline is due to three main factors: First, the Nord Stream 1 pipeline was shut down after being bombed and remains shut down until the date of writing this study. Second, the cessation of gas pumping through the Yamal pipeline, which crosses Polish territory, which halted the transit of gas from its territory. Third, the significant increase in gas prices, which prompted Norway to increase production capacity[6].

LNG imports

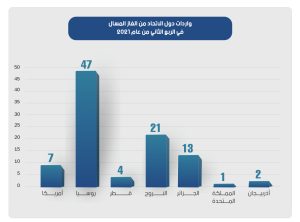

Liquefied gas (LNG) is an important source of consumption in European Union countries. The combined production capacity of European LNG plants has reached 237 billion cubic meters annually (this figure includes production from the United Kingdom and Turkey), which is sufficient to cover nearly 40% of annual gas demand.[7] In this section of the report, we highlight European LNG imports. Figure (3) shows the LNG imports of European Union countries in the second quarter of 2021.

Figure (3) European Union countries’ gas imports in the second quarter of 2021

According to Figure (3), we find that the Russians were the largest exporters of liquefied gas to the European Union countries, as is the case via pipelines in 2021. After the Russian war on Ukraine, the equation changed, as Europe’s total imports of liquefied gas increased by 10% compared to before the war on an annual basis in order to compensate for the interruption of Russian gas imported via pipelines. The United States emerged as the largest supplier of liquefied gas to the European Union with a share of 45% (17 billion cubic meters), followed by Russia (18%, 5.8 billion cubic meters) and Qatar (13%, 4.9 billion cubic meters), as shown in Figure (5), the European Union countries’ imports of liquefied gas in the second quarter of 2023[8].

Figure No. (4) European Union countries’ imports of liquefied gas in the second quarter of 2023

According to ENTSO-G – the European Network of Gas Transmission System Operators – the European Union has become the largest importer of liquefied natural gas in the world after the Russian war on Ukraine. In the second quarter of 2023, Europe imported 22% of global liquefied natural gas imports, ahead of China (18%) and Japan (14.9%). France was the largest importer of liquefied natural gas in the European Union, followed by Spain and the Netherlands[9].

We conclude from the first section of the study that EU countries’ dependence on Russian liquefied and natural gas was very high in the period before the Russian war on Ukraine, and Moscow’s monopoly was highly dangerous. This dependence has decreased significantly since 2023, after Europe adopted the policies and strategies discussed in the second section of the study. Imports of non-Russian liquefied gas increased, and with them imports from other non-Russian pipelines. Thus, we are witnessing a decline in the degree of dependence of European countries, not a complete end to their dependence on Russian gas. We also conclude that, in the medium term, many European countries are not expected to end their dependence on gas from Moscow. We also conclude from this section that the United States has emerged as a long-term strategic supplier to the European market.

Second: The infrastructure for gas consumption and import for European Union countries

In this section of the study, we focus on European infrastructure related to gas production and consumption, which, in understanding this, reveals their ability to diversify their imports and the possibility of eliminating dependence on Russian gas. We also discuss potential alternatives capable of meeting European demand, primarily the United States, Qatar, and Algeria. We also review the energy policies adopted by European Union countries to reduce their consumption of Russian gas. The European Union strategy, developed in recent years, aims to reduce dependence on Russian gas. This strategy is primarily based on diversifying gas import sources rather than over-reliance on a single source, developing and establishing infrastructure capable of receiving additional shipments of liquefied and natural gas, and diversifying energy consumption sources, as European countries seek to increase renewable energy production.

As we explained in the first section, European countries have historically relied on natural gas coming through Russian pipelines. Therefore, some countries, such as Germany, were not ready to build gas liquefaction plants. Before the war on Ukraine, Europe had 21 gas liquefaction plants, seven outside the EU: three in the United Kingdom and four in Turkey. The plants are distributed as follows: Belgium has one plant, France has four plants, Greece has one plant, Italy has three plants, Lithuania has one plant, Malta has one plant, the Netherlands has one plant, Poland has one plant, Portugal has one plant, and Spain has seven plants. The combined capacity of these plants, as we mentioned in the first section, is 237 billion cubic meters annually. This number includes the production of the United Kingdom and Turkey, which is enough to cover nearly 40% of Europe’s annual gas demand[10].

Following the war on Ukraine, European countries have moved to develop their gas import infrastructure. We summarize the new policy as follows:

Poland has begun expanding the capacity of its Soniajce re-liquefaction terminal, Italy is developing a floating liquefaction terminal, and Greece is developing a new storage and re-liquefaction unit in the port of Alexandroupolis. The Netherlands has established the Ems liquefaction terminal, capable of supplying a total of 8 billion cubic meters of gas annually to the national natural gas grid and also supplying gas to neighboring countries such as the Czech Republic. Germany, one of the world’s largest gas importers, imports almost all of its gas consumption from abroad. Russia was the primary source, accounting for approximately 55% of its total gas consumption. Germany is currently witnessing significant development in its gas liquefaction infrastructure. Chancellor Scholz announced that Germany is building three onshore gas liquefaction plants. The first, near Brunsbüttel, has a re-liquefaction capacity of 8-10 billion cubic meters per year and could be operational by 2026. The second is the Wilhelmshaven GmbH LNG plant, and the third project is located at the Stade Hanseatic Energy Hub. The three onshore plants require time to complete the construction process and could take between 2 and 3 years. Berlin has also leased five floating liquefaction units, which have been operating since the beginning of 2023. Germany’s annual gas liquefaction capacity has reached approximately 25 billion cubic meters, equivalent to half of the amount imported from Russia. The total capacity of the newly established European stations has reached approximately 50 billion cubic metres, and these stations will play a pivotal role in reducing dependence on Russian gas and achieving the import diversification policy[11].

In addition to establishing gas liquefaction plants, European countries have implemented a number of projects related to internal pipelines. The construction of a pipeline linking Greece and Bulgaria was completed, connecting it to the Greek gas transmission network and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). On August 26, the gas interconnector between Poland and Slovakia was inaugurated. Its completion represents the cornerstone of the North-South gas infrastructure corridor, between the Baltic, Adriatic, Aegean, Eastern Mediterranean, and Black Seas. The pipeline is approximately 165 kilometers long. Poland also inaugurated a pipeline, which serves as a major route for transporting gas from Norway via Denmark to Poland and neighboring countries. The pipeline allows for the import of up to 10 billion cubic meters of gas annually from Norway to Poland and Denmark. These projects enhance the diversification of liquefied gas supplies from outside the continent to Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe and the Baltic states.[12]

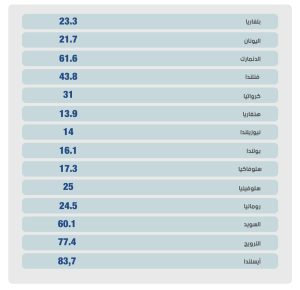

The European Union countries have also moved towards establishing and financing private projects to produce renewable energy and rely on it in electricity production, and have developed a plan to achieve the goal of zero carbon neutrality, becoming the first climate-neutral continent in the world by 2050 [13]. With the continued operation of renewable energy projects, reliance on fossil energy resources, including gas, will gradually decrease in the long term. Table No. (1) shows the extent of European Union countries’ reliance on renewable energy as a percentage of total consumption for the year 2021.

Table No. (2): European Union countries’ consumption of renewable energy

It’s clear from the previous table that the European Union’s reliance on renewable energy is considerable. Countries such as Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland have been able to cover a significant portion of their energy needs through renewable energy, which explains their reduced reliance on gas and other fossil fuels. The continued development of renewable energy sources will significantly reduce gas demand, especially given the widespread adoption of electric vehicles in European countries.

We conclude from this section of the study that EU countries have been able, within a short period of time, to develop a portion of their infrastructure for importing and consuming natural and liquefied gas. In the coming years, according to announced plans, they are seeking to expand liquefaction plants and rely more heavily on renewable energy, significantly reducing their reliance on Russian gas.

Third: Expected alternatives for European Union countries to Russian gas

In the previous section, we highlighted the development of gas import infrastructure in European Union countries, which has contributed to reducing dependence on Russian gas and replacing it with imports from the United States, Algeria, and Qatar, as we explained in the first section of the study. However, these countries’ exports peaked in 2023, meaning they no longer have the capacity at the present time to increase production to match the EU countries’ needs to reduce their dependence on Russian gas. Based on this, in this section of the study, we highlight the extent to which gas-producing countries can compensate Europe for its dependence on Russian gas in the medium and long term.

It’s important to note, before delving into the alternatives available to Europe, that the volume of liquefied natural gas currently available in international markets is not sufficient to meet the European market’s needs to replace Russian gas. Indeed, it is currently sufficient to reduce reliance on Russian gas relatively quickly. Europe currently holds the majority of spot gas contracts on international markets, so EU countries will continue to need Russian gas for at least the medium term.

First source: United States of America

The United States recently joined the club of oil and gas energy producers after pumping significant investments into shale gas and oil production. Washington possesses shale gas reserves estimated at 625.4 trillion cubic feet at the end of 2021. [14] The United States exploited the European Union’s need for gas after the decline in Russian gas imports following the Russian-Ukrainian war. As shown in Figure (4), Washington emerged as the largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the European Union in 2023, with a total of 40.5 million tons, equivalent to approximately 45% of the European market’s total LNG imports. According to the International Energy Agency, estimates indicate that Europe needs between 50 million and 75 million tons of long-term LNG supplies from the United States alone to help compensate for the decline in Russian imports. The European Union accounted for nearly 64% of total US liquefied natural gas exports in 2022 [15]. In 2022, EU countries signed deals to purchase US liquefied natural gas for 15 years or more. [16] Currently, the United States is pursuing a number of projects specializing in gas production and liquefaction, and these projects have been classified as the most ready to launch in the world. Thus, Washington will provide European markets with a significant portion of their gas needs, thus monopolizing the European market and replacing Moscow. This is one of the goals and interests that Washington has gained from the Russian war on Ukraine.

Second source: Qatar

Qatar is ranked third in the world with gas reserves of 24 trillion cubic meters, representing approximately 13.1% of the world’s total reserves, after Iran and Russia. In 2020, it produced more than 170 billion cubic meters of liquefied natural gas (LNG), making it the world’s largest producer and exporter of LNG in 2020. BP estimates that Qatar’s total LNG exports in 2020 amounted to 106.1 billion cubic meters. [17] Qatar is working on a billion North Field expansion project to increase production capacity from 77 million tons to 110 million tons annually, an annual increase of approximately 43%. [18] Production is expected to reach 110 million tons by 2025. In addition to its massive reserves, Qatar has the world’s largest LNG fleet, comprising 69 tankers and a floating storage and regasification unit.[19] In 2021, Qatar Energy signed agreements to build more than 100 new LNG carriers worth 0 billion.[20]

Qatari liquefied natural gas (LNG) has become a major pillar of European imports as it seeks suppliers to compensate for the shortage of Russian supplies. Qatar delivered 16% of its LNG supplies to the European Union in 2023, making it Europe’s second-largest supplier after the United States. Qatar, a major gas producer in the world alongside the United States and Australia, recognizes the opportunity to capture a significant share of the European gas market. Several European countries have signed contracts to purchase Qatari LNG, the most significant of which is a 15-year supply contract between Qatar Energy and Germany. The agreement stipulates the supply of 2.5 billion cubic meters of Qatari gas annually to the German market, starting in 2026.

Third source: Algeria

Algeria is classified as a country with strategic weight in the international gas market, due to its reserves and high production capabilities, as it has reserves estimated at 4.5 trillion cubic meters according to data for the year

2019 [21], and its production amounted to about 130 billion cubic meters in 2019, according to data from the state-owned company “Sonatrach”, and Algeria exported more than 51 billion cubic meters in the same year [22].

Algeria is currently the second-largest supplier of natural gas via pipelines to Europe after Russia, exporting more than 36 billion cubic meters in 2023, according to official figures from Sonatrach. Algeria is connected to Europe via three pipelines crossing the Mediterranean: the first passes through Tunisia to the Italian island of Sicily; the second passes through Moroccan territory to Spain, and is currently suspended due to the political crisis between Morocco and Algeria; and the third passes through Almeria in southern Spain. Algeria could increase its exported volume by restarting the suspended pipeline, in addition to increasing liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports. Algeria has announced a series of gas field development projects, which are scheduled to be completed in 2026 [23]. Following the completion of development operations, Algeria’s production is expected to increase, with the European market then set to be the primary recipient of pipeline readiness between the two countries, in addition to the geographical proximity that provides an advantage in the rapid arrival of LNG shipments.

Fourth source: Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan is classified as a natural gas producing country, with reserves estimated at 2.5 trillion cubic meters, and its annual gas production reached 50 billion cubic meters according to 2020 data [24]. In 2020, Turkey and Azerbaijan inaugurated the TANAP pipeline, which extends from the Shah Deniz field in Azerbaijan and passes through Georgian territory to Turkey. It connects to the TAP pipeline in the Uppsala region of Edirne, Turkey, on the Greek border, which transports gas to southern Europe. The maximum export capacity via the TANAP gas pipeline is 31 billion cubic meters annually, with 15 billion cubic meters being supplied to Turkey, while the remaining 16 billion cubic meters will be exported to southern European countries [25].

Fifth source: Egypt

According to Oil and Gas Magazine, Egypt has 63 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves, according to 2021 statistics. Cairo hopes to leverage its location and infrastructure to become a major hub for gas trade and distribution to markets, particularly the European market. [26] Egypt’s infrastructure is considered moderately efficient and robust, with two gas liquefaction plants with a combined production capacity of 586 billion cubic feet per year. The first, Damietta, is located in Damietta City and has a production capacity of 240 billion cubic feet per year. The second, Idku, has a production capacity of approximately 340 billion cubic feet per year. It is important to note that Israel exports its gas to international markets via Egypt by pumping it through a pipeline to be liquefied at Egyptian plants and then exported to international markets.

Note: The aforementioned countries have the technical and geographical capacity to export LNG to Europe. However, a country like Iran was not included due to sanctions on its energy sector and the inability of its current infrastructure to export LNG. Turkmenistan, which has 8 trillion cubic meters of reserves, was also not included because it is geographically landlocked and exports its gas only via Russia. Saudi Arabia also has large reserves but has not developed the infrastructure to manufacture and produce LNG.

As a result of this section of the study, the European Union countries were able to achieve a crucial equation that ensures a high level of energy security. This equation is based on signing long-term liquefied natural gas (LNG) import contracts with producing countries such as the United States, Qatar, and Algeria, which are working to double their gas production by the beginning of 2027. At the same time, European countries—particularly Germany—are developing their infrastructure capable of absorbing the additional quantities of LNG in international markets. With this equation achieved, the volume of the European Union’s imports of Russian gas will significantly decrease after 2027, potentially ending the monopoly that Russia has imposed on them for more than three decades.

Fourth: The implications of the shift in European energy policy for Russian energy security.

The study concluded in the previous sections how the energy policy adopted by the European Union countries has significantly reduced their dependence on Russian gas, which could have negative political and economic repercussions for Moscow, which we discuss in this section of the study.

Energy security issues and policies occupy a strategic dimension and space in the stages of Russian policy-making, as they are considered one of the main factors in making domestic and foreign policy, due to the financial revenues and basic support they provide to the state’s economy, and one of the most important tools of its foreign policy. Russia’s concept of “energy security policy” is based on the fact that gas and oil reserves do not have any influential power if there is no demand and high prices for them, and this requires always searching for new markets for export [27]. Gas sales are considered a matter of great importance to the Russian economy and are the primary source of funding for the state treasury.

The European gas market is considered the most important for Russia, given that it is one of the largest consumers in the world. Therefore, Moscow seeks to maintain its monopoly over the European gas market through a strategy of linking it with a group of pipelines. This is a policy of “pipeline interconnection.” Russia recognizes its geographical proximity to European countries, which facilitates the process of extending pipelines, and is considered more efficient than other means of transportation, as we explained in the first section of the study. The interconnection policy implemented by Moscow has presented European countries with a reality and economic feasibility that compels them to import Russian gas. In this section, we illustrate the Russian pipelines that connect to Europe in Map No. (1): Energy pipelines from Russia to Europe and Turkey.

Map No. (1): Energy pipelines from Russia to Europe and Turkey

– Yamal Pipeline No. (1): It extends from Russia through Belarus and Poland to Germany, and the annual export capacity is 31 billion cubic meters [28]. This pipeline is not operating at the present time, due to Poland stopping work on it after the Russian war on Ukraine.

– Trans-Ukrainian pipelines No. (2-3-4) where three main pipelines – which pass through Ukrainian territory – transport natural gas from Russia to the European Union countries. These pipelines are classified as the largest gas transport corridor with an estimated capacity of more than 46 billion cubic meters annually, through which Russian gas can be delivered to consumers in various European countries via internal networks. The gas transport agreement across Ukrainian territory expires at the end of this year, as no official statements have been issued by the countries concerned regarding the renewal of the work agreement on these pipelines until the date of writing this study. However, it is expected that the pipeline work agreement will be renewed due to the European countries’ need for the quantity imported from Russia via these pipelines[29].

The fourth pipeline, Nord Stream, extends from Russia directly across the Baltic Sea to Germany. It consists of two parallel pipelines. This pipeline is strategically important for Russia, due to its capacity to transport 55 billion cubic meters annually, or 37% of Moscow’s exports to EU countries. This project aims to bypass transit countries, particularly Eastern European countries. This will cause some countries to lose annual pipeline transit fees, and gas exports will reach Western countries directly.

Line No. 6 was operating, but it stopped after it was bombed in international waters, while Line No. 8 has not yet been completed due to American opposition to this project[30].

– TurkStream Pipeline No. (9), extends from Russia to Turkey via the Black Sea and branches into a line designated for Turkish consumers, and a second designated for southern and eastern Europe. The quantities transported through it in 2020 amounted to 13.51 billion cubic meters[31].

– The Turkish Blue Stream Pipeline No. (7) exports gas from Russia to Türkiye only.

– Line No. (5) is an old pipeline that has stopped operating since the fall of the Soviet Union[32].

The policy of networking and monopolizing the European gas market has contributed to the Russians gaining leverage against the European Union countries. Putin always uses energy resources as a weapon against European countries, by cutting off supplies, as happened in 2006 and 2009, when Russia stopped the transfer of gas through Ukraine, which prompted the European Union to pass important legislation in 2009 to confront the cessation of Russian gas supplies[33].

According to the study’s data, the EU’s declining dependence on Russian gas threatens to cause Moscow to lose its share of the European gas market, forcing it to seek new markets. However, finding a quick and financially attractive alternative with the same capacity as the EU seems unlikely at present. Currently, the Russian company Gazprom cannot redirect gas extracted from the fields of West Siberia and the Yamal Peninsula to countries outside Europe, and there are no gas links that would allow it to export these quantities to Asian markets such as China. The only current pipeline through which Gazprom can export gas to China is the “Power of Siberia” pipeline, launched in December 2019. Pipeline No. 10 (as shown in Map (1) of the Energy Pipelines from Russia to Europe and Turkey) is not connected to the gas network in western Russia. Through Gazprom, Moscow is attempting to build a new pipeline—Power of Siberia 2—to export gas via Mongolia to China. This pipeline will allow the export of 30 billion cubic meters of gas annually from the fields of West Siberia. Moscow is discussing the use of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan as transit countries for Russian gas exports to China, but no actual agreement has been reached at the time of writing. Russia still has the opportunity to increase its exports by exporting liquefied gas to global markets, particularly China and India. Moscow currently has several liquefaction plants, the largest of which are the Yamal LNG terminal on the Yamal Peninsula and the second, Sakhalin-2, in the Far East. There are also smaller export terminals in western Russia: Kryogaz, Vysotsk, and the Kansas-Portovaya plant. In contrast, the countries to which Russia intends to export gas must establish liquefaction plants capable of receiving Russian gas. For example, China has liquefaction plants that receive liquefied gas from Qatar, the UAE, and many other countries under long-term contracts. It is unknown how much of China’s capacity to receive large quantities of Russian gas will be. It is important to note that China is trying to reduce its consumption of coal, which accounts for 71% of total energy consumption, and gas is an alternative to it. [34]

Conclusion:

Following its war on Ukraine, Russia used its energy resources as a bargaining chip against the European Union. However, Moscow was confronted by EU countries’ adoption of policies and strategies aimed at reducing their dependence on Russian gas and ending Moscow’s monopoly on their markets. This was in addition to their desire to deprive Putin of financial resources from the gas trade, which is one of the country’s most important resources. In the period following the Russian war on Ukraine, European countries were able to change some of the rules of the game with Russia regarding its monopoly on the European gas market. The game has shifted in favor of European countries—for the time being, at least—with the support of the United States, which encouraged and pressured Europe to halt imports of Russian gas and replace it with American liquefied natural gas. Washington thus became the largest source of liquefied natural gas to the European market, thereby reducing the pressure that Russia had historically exerted. As an important conclusion of the study, we concluded that the United States has been the greatest beneficiary of the gas war between Russia and European countries. American shale gas producers are on the rise, which will eventually lead to a monopoly on the European gas market, replacing Russian companies. Washington no longer has a stake in Europe’s return to importing Russian gas as it did in the past, especially after it launched a large number of gas production projects.

The data we reviewed in this study confirms a decline in European Union countries’ imports and consumption of Russian gas. However, the decline came through pipeline gas imports, particularly after the Nord Stream 1 explosion. On the other hand, Russian liquefied gas imports are on the rise again, and thus we are faced with an unequivocal conclusion: European countries cannot completely dispense with Russian gas in the medium term. Rather, in the long term, they can reduce their dependence on it after a number of European countries complete the construction of liquefaction plants, in parallel with the development of gas-producing countries such as the United States, Algeria, and Qatar, in addition to the development of renewable energy projects.

The study concluded that Russia has lost a significant portion of its market share in the European market to the United States and other countries such as Algeria and Qatar. Moscow is now seeking new markets in Central and East Asia, but exporting to these countries requires developing infrastructure for both Russia and the importing countries. Thus, Moscow has lost a significant portion of its financial resources coming from exporting gas to European countries. It is widely expected that EU countries’ dependence on Russian gas will decrease after 2027, a date that will witness a rise in global gas production. By that date, EU countries will have developed an infrastructure capable of accommodating LNG quantities double those absorbed in 2024.

It is important to note that one of the drivers of the decline in EU imports of Russian gas is the decline in industrial demand for gas in Europe, which has also been a major factor in the stability of gas prices. Any reversals in demand could disrupt the supply-demand balance in the European gas market, potentially leading to higher prices and a renewed surge in demand for Russian LNG.